Reports of extortion in Colombia have increased 229 percent in the last four years, as guerrillas, mafias and street gangs cash in on a market believed to now be worth over a $1 billion a year, according to an El Tiempo investigation.

In 2012, there were 2,316 reported cases of extortion, up from 830 in 2008, although police believe this represents only around 20 percent of actual cases, reported El Tiempo in a special investigation into extortion in Colombia’s main cities. According to the 2012 National Victims Survey, 125,000 Colombians reported paying protection money or being victims of extortion attempts.

The overwhelming majority of cases — 83 percent — were attributed to “common criminals.” The guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) accounted for 9 percent of cases, while groups such as the Urabeños and the Rastrojos (labeled “BACRIM” by the government, from the Spanish for “criminal bands”) accounted for 6 percent, and the guerrillas of the National Liberation Army (ELN) 2 percent.

Nearly half of the victims were business owners. The rest came from a broad range of sectors including bus drivers, cattle ranchers, politicians, students and even the security forces.

As well as these traditional targets of extortion, Colombia also now suffers from “cyber extortion,” with criminal groups tracking down personal data on the web then threatening to make it public.

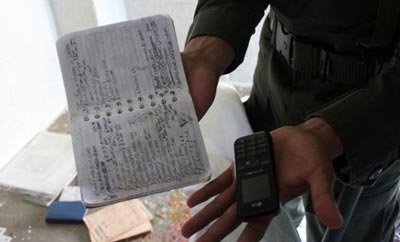

The most common method of extortion was by telephone, which was used in 50 percent of cases. In 24 percent of cases, payments were demanded in person, and in 19 percent a mixture of both methods was used.

The Colombian city worst hit by extortion is Medellin, followed by Bogota and Cali.

InSight Crime Analysis

Extortion has long been one of the main sources of income for Colombia’s guerrilla and paramilitary groups, who charge a “war tax” to fund their fight. However, while the guerrillas are renowned for targeting land owners and businesses operating in remote and rural areas, it is in the cities where the situation currently seems to be deteriorating.

In Colombia’s cities, it can be difficult to know where “common criminals” end and the BACRIM begin. Street gangs may use the names of bigger criminal organizations to instill fear and compliance in their victims, while the bigger organizations often contract out work, including extortion, to the gangs or take a cut of their profits.

What is clear is that large criminal organizations such as the the Urabeños and the Rastrojos are not content with the lucrative profits from the international drug trade. This desire to profit from all types and levels of organized crime, together with the unchecked growth of street gangs in cities like Cali, is likely to be fuelling the extortion explosion.